There is an art to never looking anyone in the eye. It's an apparition of deference. It's more about retaining one's own integrity than it is about acknowledgement of a superior. The people in the jungle never look outsiders in the eye. Outsiders are other people, with strange and dangerous ways, they come to kill, to flog, to maim, to control, to train, to teach - but never to share.

Lorna Mulrooney had learned the style of not looking, but she had not learned the art. For her to look down or away was true recognition of her lowly place in the village hierarchy.

And so it is with this deference that she and Amy leave their tent and, slightly stooped, walk almost crabwise towards the centre of the village and to breakfast. Approaching the Culinierre, they crouch low, hold their bowls upwards and turn their bodies away.

Always there is a pause. The Culinierre will look around the assembled villagers for a nod or a shake of their heads, seeking consent as to whether these outsiders should be fed. Almost always now, the pause is following by the slop of the breakfast stew into the wooden bowls. Rarely do Lorna and the girl go hungry.

At first it had been different. Within the first month their supply of dried food had been used up. Now a small tin of hardtack was all they had in their tent and if they had to skip a meal they went hungry. The hardtack was their last link with the rest of the world, a link that in an emergency would feed them for perhaps three days.

The slop of the food into the wooden bowls and they crouch their way a respectful distance from the Culinierre before sitting on the ground and spooning heaped mouthfuls of the banana and meat. There is murmuring all around and the soft clunk of wooden spoons on wooden bowls as the village comes awake and gathers, in small groups, to meet the new day with food.

There is less tension in the air than when they first arrived, stumbling into the village, having lost the pastor who was leading the mission.

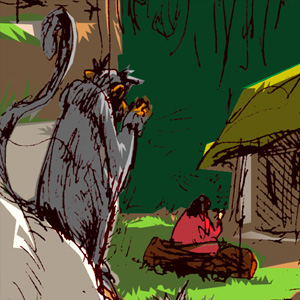

A tiny but rambling village, no more than a couple of dozen shacks, or huts or sheds. A mish-mash of brick and stone and rough-cut planks. Roofs of corrugated tin, some even of palm leaves still, some a mix of both where thatch has been patched with tin or tin patched with thatch. They eat, and they wash their bowls and they wash themselves at the river.

Amy wanders among the children, almost at one with their ways of play. She is happy to help the other children as they skin and gut a boar or a monkey to be cooked later. She gathers berries and leaves with them. Lorna busies herself with unasked tasks, straightening logs for the fire, carrying ashes from the fire to the shit pits.

Sometimes a villager will give her a troublesome baby to entertain, or she will find herself with all four of village's infants when there is a major task at hand. And the days slip by - and little by little, Lorna steps closer to the heart of the community, despite her strangeness, she feels herself drawn to the passion, the heart, the embrace of these people who live as if in another century.

Somewhere, sometimes close, exasperatingly always out of reach, there is waiting the embrace of fear and passion, of love and dread.